“Suck a Dick” and Other Nice Things We Say Online

Two weeks ago, I made a snarky comment on Twitter, about Donald Trump. In retrospect, this was a bad call. For anyone who read the thread, it was clearly a joke. But, some didn’t want to take the time to read. Instead, they leapt into a tirade of name-calling, threats, and hate speech. Eventually, I deleted the tweet. (It was kind of dumb, and wasn’t worth the grief.)

Trolls, trolls, and more trolls

I don’t want to make a big deal of the experience, but it’s far from an isolated case. That same week, I tweeted about the glut of superhero movies. (For the record, I enjoy these flicks—but there sure are a lot of them.) This led to a torrent of folks telling me to, “suck a dick,” and such. Maybe I shouldn’t be surprised, but I sort of am. What exactly are these folks so upset about? That one unimportant middle-aged guy mocked a film genre they like?

There are certainly issues to feel outrage over. However, the ones we get most upset about are often trivial ones. I do this, too. Someone posts a video of a jerk driving recklessly, in some other part of the world, and I feel compelled to say something. But why? It’s not like such content affects me in any way. And even if it did, what change will come from me adding one more comment?

So, I tried something else

When I receive hostile responses on Twitter, I typically reply with a cheeky animated GIF. Like this:

this:

or this:

Doing so serves as a workable retort, and allows me to have a little fun. But, it can also have the opposite effect—which leads to some unpleasantness. (Sam Altman recently noted that his best productivity tip is to, “Never, ever, get in fights on the Internet.”)

Lately, though, I wondered if there might be a better way. Could I diffuse web arguments by responding differently? So, for a stretch, I tested this. I posted some non-confrontational things on Reddit, and watched the comments roll in. As one might expect, about half were just fine. The others were more antagonistic. (For the record, I appreciate critical remarks, but find sheer hostility non-productive.)

This time, I responded to belligerent comments unemotionally, and asked questions. I also took more time to explain my position. Essentially, I did what I would at a dinner party, at which I disagreed with another guest’s perspective—but didn’t want to spur an argument.

My findings? Aside from with people I already knew, it didn’t work. My hunch is that folks actually like arguing online—and, even more so, the “pile on.” Again, though, my question is: why?

The illusion of connectedness

We live in a world that’s increasingly—superficially—connected. Take, for example, LinkedIn. Consider all those who you’re “connected” to, on that network. Now, how many could you reach out to with a request, and reasonably expect a response from? My bet is few: because LinkedIn’s key concern/metric is growth. It simply isn’t built to encourage meaningful interactions.

The more I use social media, the more I think that we’re all just pretending to be connected with one another. We’ve achieved a semblance of kinship, without any of the fidelity. This leaves us wanting for something that should be implicit—but is missing from the paradigm we all bought into.

Empty calories

I watched/read a bunch of nutritional films and books over the past while. In doing so, one concept stuck with me. It’s the idea that the problem with processed food is in how our body reacts to it. This material is so barren that our body sends our brain a message: keep eating. As a result, we eat way more empty calories than we should. The people behind this notion propose that we should instead eat more nutritionally dense food. They believe that doing so will curb these cravings—because, once fuelled, our bodies stop asking for more.

I’m not a nutritionist, so I don’t know if the above is actually true. That said, it seems like a reasonable enough proposal. Let’s apply this same notion to social media. The content we consume in this space is like junk food. Even Ev Williams (former CEO of Twitter) agrees, noting: “We put junk food in front of them and they eat it.”

What if our minds seek something meaningful, online, but can’t find it? Could this be why we compulsively return to social media feeds, gobbling up any new morsel we see? And, as these so rarely leave us satisfied, do we simply consume more, in hopes of filling a void? One more question: Is our quickness to leap to outrage not about anger—but instead about wanting to feel something… anything?

This isn’t working

Again, there are plenty of things to be angry about (e.g. environmental negligence, racial injustice, widening economic inequality). However, these aren’t the matters we talk about most. Instead, we seem to hone in on trivial topics (e.g. blue/gold dress, Kardashians, whether Ford trucks are better than GMCs). These are easier, as they allow for snap-judgements.

We quickly pick a side and then disparage the character of those with another viewpoint. This isn’t—in any way—beneficial. We don’t learn anything from these shouting matches. These exchanges don’t broaden our perspectives. In fact, this activity tends to divide us further—which is the opposite of what we need.

I blame two factors for the downward spiral of online commenting and communities. (Note that I’m referring to the nature of these communities—not their growth velocities.) The first is anonymity. Fact is, many people behave worse when their identity is hidden. We see examples of this in varying communities’ policies and the activity that takes place within them. For example, comments on YouTube and Reddit tend to be worse than those found on Facebook—because the consequences of being a jerk are greater, when you are among people you know.

Second is the absence of house rules. Aside from discouraging outright illegal activity, networks like LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter have pretty laid-back policies. In fact, many of the current social networks benefit from bad behavior. The more heated the discussion, the more likely you are to return to it. (This, of course, works in the interests of the network, which needs page views in order to generate revenue.) Over time, though, this same activity becomes toxic. And, at the scale these networks operate at, the possibility of making this less so is unlikely.

Could we do better?

Social media is a powerful vehicle, but I argue that it’s still not mature. In its current state, it excels at distraction—but none of us need more of that. Similarly, it tears us apart, instead of helping us better understand one another. I say this opens up an opportunity for us to make something better. In fact, I feel that there’s an onus—on those of us who build stuff—to make that happen.

We’re doing this with Officehours which started as a way to connect people, who don’t know one another—for a 10 minute meeting. At first, we thought this was about mentoring. Upon using it more, though, we realized it wasn’t that hierarchical. It’s not about handing knowledge down. It’s about two people building a connection. These opportunities go both ways.

In time, we realized that we were building something bigger. We started thinking that this could become a new kind of professional network. The point here isn’t to brag about accomplishments or post business-like content. Instead, it’s to build meaningful connections. One-to-one interaction is key to that, and it’s sort of transformative. I’d never ask someone on LinkedIn for advice; but, I feel comfortable doing so on Officehours. Better yet: at the end of these sessions I feel like I actually know the person I just spoke with.

Next up

We have a lot of work to do on Officehours. This week we’re rolling out new pages for some of our more popular categories. Soon after, we’ll release team pages for organizations. We’ve planned out much of how Officehours will develop, and we have a solid roadmap in place for the year ahead.

Lately, I’ve worked most on ways to fix what I feel is broken in other networks. The first is a welcome mat of sorts. It’s part of an effort to encourage civil, gracious, and constructive interactions. We’re so serious about this that we’ll actually suspend users who are hostile, or only in the community to promote themselves. (Think about it like a house party. If someone shits on your kitchen table, you’ll ask him/her to leave.)

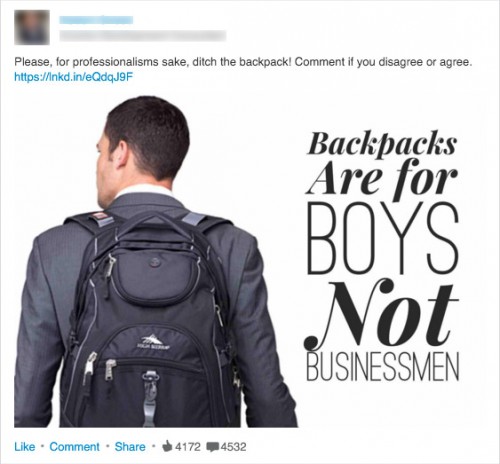

Then, we’ll move on to streams. I bet that you’re pretty tired of seeing things like this:

this:

and this:

…in your LinkedIn feed.

So, we’re taking a different approach from most other social network feeds. In ours, new content is categorized at the get-go. This means less work for the person browsing content. (Every user will be able to customize streams to his/her specific liking.) Additionally, we encourage only certain types of content. If it works, this will help us cut out the humble-brags, self-promotion, and inane junk.

An invitation

I’ll post more about what we’re doing with Officehours, in the future. In the meanwhile, though, I wanted to reach out to you first. You’re one of a small handful of people who read the articles I write. As such, I figure that you likely share some of my perspectives. We’re looking for people like you to take part in this new community, and to assist as we build out these features. Before you join, though, a few of our house rules:

Practice generosity: Start by opening your door. Offer some recurring sessions (maybe one or two a week) and lend a hand to those who need it.

Keep learning: Request a session on Officehours, once a week. This helps you meet new people and learn new things.

Be respectful: If you dislike someone’s viewpoint, challenge it—but avoid trolling and name-calling.

Sound good? If so, please, sign up for a personal account. Organizations can also request/reserve their team page.

I do hope you’ll join us. :-)

I’m @karj and the above is just my opinion. Looking for more? Here’s a full list of articles and information on my books. This is what I’m doing now, and what I don’t do. I’d love it if you tried Emetti on your website!